- Home

- Leanna Conley

War Stories

War Stories Read online

War Stories: A Father Talks to His Daughter

by Leanna Conley

Copyright © 2012 by Leanna Conley

Illustrations Copyright © 2012 by Leanna Conley and M.A. Zavoy

All rights reserved.

eISBN 978-0-9771102-7-8

This book may not be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in whole or in part, without permission in writing from the publisher: Pelican Press Pensacola, a subsidiary of The Pelican Enterprise, LLC, Pensacola, Florida.

Pelican Press Pensacola

P.O. Box 7084

Pensacola, FL 32534

www.pelicanpresspensacola.com

For Bill

When you go home,

Tell them of us and say:

For your tomorrow,

We gave our today.

Inscription at Kohima Memorial, Burma, 1944

Table of Contents

The Water Bag

Diary Entries: May 22, 1942 and April 1, 1943

Drivin’

Diary Entries: November 23, 1943, and April 29, 1945

The Ring

Diary Entries: November 7, 1944, and December 29, 1944

The Jeep

Diary Entries: January 15, 1944, and August 26, 1944

The Little Lion

Diary Entries: June 1, 1944, and July 24, 1945

The Jacket

Diary Entries: May 3, 1944, and December 23, 1944

The Orange

Diary Entries: July 21, 1944, and September 1, 1944

The USO Show

Diary Entries: December 13, 1943, and January 17, 1944

The Baseball Game

Diary Entries: August 6, 1945, September 3, 1945, and November 29, 1945

The Last Story

The Elephant Epilogue

About Bill

Acknowledgments

War Stories: A Father Talks to His Daughter

Picture the era.

Jazz hit “Poor Butterfly” plays on a 1940’s radio and resonates throughout the Carousel Hotel in Cincinnati, Ohio—the same song that Tony Bennett (who served in WWII under his real name, Tony Benedetto) would record later in the 1960s.

Let me tell you about the story of a little Japanese,

Who was sitting demurely underneath the cherry blossom trees…

Butterfly her name….A sweet little innocent child was she,

‘Till a fine young American from the sea, to her garden came…

In the old landmark hotel, unshaken by history, men line up for deployment and get their pictures snapped with loved ones, some for the last time. The mood is light. The boys unfazed. That is the way of their generation.

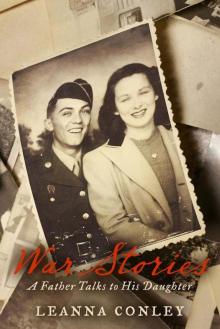

The guy in uniform is my dad, Bill Taylor. He is a hottie—a Leonardo DiCaprio of the ’40s. That’s his first wife, Diana, next to him. (Don’t tell my mother I used Diana’s picture.) They’re standing in front of the wall of the hotel lobby, with its picturesque Greco-Roman wallpaper. The colors are undoubtedly brighter than this picture can show. This shot is taken just before his deployment in 1942. He has just turned nineteen.

As a young man, Dad’s charm and love of life were constant. If we were with him as a part of that scene, we would all be partying and having a wonderful time. He was so amazing to talk to, so knowledgeable about everything. My best friend. Even as he got older, his optimism and ebullience were ever-present. He had lived through wars and wives and the Great Depression, and still, whenever I called him at home in Detroit from my studio apartment in New York City, he’d answer with the usual:

“Taylor.”

Hi, Papa!

“Oh, good morning, honey! How’s the career coming?”

[Pause…]

“Oh, it’ll hit. I just know it!”

[Pause…]

“How’s that friend of yours? What’s his name?”

Paul. We’re not seeing each other…

“Oh, he dumped you? Good riddance!”

One thing I loved as a child was listening to Dad’s war stories. They were not your run-of-the-mill, blood-and-guts tales: “Me and Joey was surrounded by 10, no 100, no 1,000 Japs, and we wiped ‘em out, machine guns a-blazing.”

Nope. No heroics for him. He was a simple man with a genius IQ, studying engineering at The University of Cincinnati when war broke. Many college or high school kids knew war was imminent, however, and, like Dad, joined the Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC). He was a member of an elite drill team called the National Society of the Pershing Rifles and received their Silver Achievement Award medal. (General Colin Powell was also a member during the 1960s in a New York detachment.) Dad had a lot of promise as an officer—he placed in the top percentile of The Army General Classification Test (AGCT), a test all draft-eligible men took at the time.

Dad in his Pershing Rifles drill team, Company E, 1st Regiment.

He’s smack in the middle.

But after participating in the ROTC, he later opted for a more technical role and enlisted in the Army. His first stop was basic training and Signal School for six weeks at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey (where they learned radio communications). Afterward, he was transferred to Camp Crowder, Missouri, for Code School. While there, he ranked as Private Taylor, 5th Grade Technician, Company A, 28th Battalion, and eventually became a JASCO—a Joint Assault Signal Company Operator.

As a JASCO, Dad was assigned to various Army and Marine divisions, setting up communications (both radio and telegraph)while working as a cryptographer. In other words, he deciphered enemy code. Sounds kind of mysterious, but he was just “Dad.”

He also did some “unmysterious” things—such as answer phones, like the operator in old black-and-white movies: “Glad to connect you, General, sir.” And, he had a secret clearance. So he could get liquor and rations when most guys couldn’t. Needless to say, Dad was very popular.

That entire generation seemed so detached from the war. The stoicism came through in almost all their stories:

“Heard about Artie? He lost his brother in the Bulge, not much of a talker, but a hell of a guy.”

“Bad break.”

“Yeah. Bad break.”

Despite Dad’s aversion to conflict, he ended up in many of the major battles of World War II. If you asked him about it, though, he’d say, “I danced with Dorothy Lamour at the USO party.” Or, “I remember Shorty Morgan—short guy.”

But, during the winter of 1998, everything changed. On Christmas Eve, one week after he was tested for cancer, we called the lab for the biopsy results. After a festive evening of opening presents and finishing a big dinner, my mother, Jeanette, my father and I couldn’t wait any longer… Bracing ourselves, we waited on the phone line.

And, what we feared more than anything was true: His tumor was malignant.

Shortly thereafter, we drove every three weeks to the Comprehensive Care Center at the University Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for chemo treatments.

As my father began the fight of his life, his once innocent stories became more vivid, more real. He went beyond his usual jovial detail. And I began to hear a whole different set of war stories than I had heard as a young girl. Like this one, about the water bag.

The Water Bag

Dad’s mood was positive. We had just visited our oncologist at The University of Michigan, who had given Dad some hope about his treatment, and we decided to dine at the Gandy Dancer in Ann Arbor to celebrate.

“We landed on Omaha Beach after D-Day to set up communications wires. We camped along a river, eight miles in from the beach.”

Dad, what was it like? On the beach?

“The countryside was beautiful, if you didn’t count the bodies.”

Bodies?

“Yeah, they came into the rivers. The ocean brought them in with the t

ide. After we set up, I remember there was this one kid who just kept staring at the water. He couldn’t even move.”

Why?

“Because that’s where they were floating.”

Wow.

After sipping his Perrier, he continued.

“Did I ever tell you about these huge water bags we used? We collected fresh water and hoisted them up on sticks, about 20 feet or so.”

No…um…you haven’t. But what happened to that man, Dad?

“Yeah. He was sweating like crazy, and seemed out of it.” Without skipping a beat, Dad said, “I’m still ravenous! Where’s our waiter?”

Pop…

“You know, it was the hedgerows that slowed our advance into Normandy. Not the Germans…”

The Bocáge, or French farmland, had hundreds of small fields with planted hedgerows—high earth mounds with trees on top. Unfortunately for the Allies, they provided perfect defensive cover for the Germans.

And…

“I was on watch. It was after dark, and the kid started screaming and firing his machine gun into the water bag. Just went absolutely nuts. He was giving it all he had, like it was the devil. We took cover, and he was still firing.”

So, what did you guys do?

“We knocked him out. Next thing I heard, he was transferred to a hospital in England.”

That’s all?

“Yeah.”

The waiter approached. “Great! More snap peas,” Dad smiled.

Okay, Dad.

From the Diary of William B. Taylor

May 22, 1942

I’m staring at pictures from HQ of the road to Bataan. Weak and dehydrated Filipino and American soldiers are walking in line, defeated, unsure of what lies ahead. Something else in the photograph catches my eye—lump after lump in the roadside ditches. When I strain, I can make out GI boots and fatigues. One GI is kneeling in front of the masses of walking American POWs. A Japanese officer stands over him. He didn’t make it to the next frame. In another picture a POW is getting his head hacked off with a Japanese samurai sword. He looks like Frank Goddard from my senior class but that’s impossible. His body is still as he faces death, quiet in its hopelessness. That moment before… How do you do it? Get through something like that? God’s grace? I just can’t know. A few feet away, in the rows of soldiers watching, the Jap officers are laughing.

April 1, 1943

We’d been driving for hours it seemed. I had C rations, some cold coffee. The water supply was already getting contaminated. I heard the crack of rifle fire like I did at Ft. Monmouth. Bullets whizzed over my head from snipers. It was surreal. The training kicked in. We hit the bottom of the truck bed all crammed in. The metal floor was hot against my face. Tony, our driver got spooked and we took off with a jerk. Pinky almost rolled out of the truck. We were laughing our heads off when the gunfire really started cracking. A few seconds later we heard screams from the rear of our column. The truck behind us started to flame up. I jumped out, put out the fire and went to the driver’s side. The kid was bloody. I threw him in the back and drove from the running board using the mirrors and popping up when I could. I floored it and caught up to Joey and the guys. Later some old brass said I did a good job and gave me a bar. What was I supposed to do? Leave them to burn?

Drivin’

After chemo we sped along in Dad’s new Ford Suburban truck, heading home, east to Detroit passing the three-story high Uniroyal tire on I-94, Motown’s version of a Marcel Duchamp ready-made. Dad wore his new leather jacket and a skull-patterned do-rag to complete his newly surfacing biker personality—and to cover his now balding head.

Dad, you were in Germany and France, for the Bulge?

“Yup. The Battle of the Bulge.”

Why the bulge?

“The Germans were coming at us from all sides.”

So, it wasn’t like a full advance, where you could see all of them at once?

“No, they had been building up in the Ardennes, between France and Germany, for weeks, squeezing us in. And they used local radio to communicate—we had a hard time patching in to know where they were, so we were totally caught off guard. Even their code word for the attack “Watch on the Rhine” was misleading.

Really?

I was outside Paris when my command said it was too risky to stay—the Germans may break through our lines at any time. Trouble is, they threw me right into the fire—transferring me into the thick of it! ”

Oh no, Dad.

“Yeah, I had a secret clearance. That’s why they moved me initially.”

Wow.

“I was attached to the 106th Infantry Division then. That’s the group Patton’s 3rd Army eventually rescued.”

Did you see Patton?

“Yeah. He looked just like George C. Scott.” Dad laughed.

Wow. Did everyone in your group have a secret clearance?

“Well, all cryptographers did. So, that night they transferred me to the Ardennes. When I woke up the next day, it had started. Already 10,000 dead…that was the morning of December 16th, 1944.”

Ohmigod.

“My unit was on the interior. Our poor guys on the front lines got it first. We were just overrun by the sheer volume of the German buildup.”

What did you do?

“I burned documents, destroyed equipment we couldn’t carry. There was classified information we couldn’t let them get their hands on.”

And then what? How did you get out?

“Convoy.”

That sounds kind of ‘70s, Dad.

“Yeah, but in this one I was on the running board of a truck with bullets firing over my head. Kind of neat.”

Neat?

“Most were teenage kids. It was exciting to a lot of them, mainly because they were new and hadn’t gotten a graveyard shift yet. The old bag ‘n’ tag.”

Bag‘n’ tag?

“You matched heads, arms, legs and put them all in a body bag, then kicked the dog tag into the teeth so it stuck.”

Dad, that’s gross.

“Yes, it is. Hand me my new skull pin, would ya?”

So, how did you get out?

“We rode 85 miles on whatever we could find to get out. Some tanks had to stay where they were and fight ‘cuz they ran out of gas. Now that, honey, was bad luck. Most of the 106th troops were pretty green. They did very well until they went up against the German tanks or Panzers. Our Shermans just didn’t cut it…”

You mean like in Patton? That movie wasn’t just Hollywood?

“No. But the group of us, we had it like Hollywood. We got out alive:Me, Shorty, Frank, John D., Joey and Jesus.”

Jesus? There were Puerto Ricans in the war?

“Yeah, don’t tell anyone. They didn’t all look like Tom Hanks, honey.”

The movie Private Ryan had just come out that summer. For some reason, I couldn’t watch it.

I know, Daddy.

“We escaped, so I had someone watching over me. Maybe Jesus.”

Funny, Dad.

“I know.”

November 23, 1943

I can’t help staring at this 17- year-old kid, Adam. He was from Utah. Just got shot in the head from sniper fire. He’s now lying behind a group of officers who are talking on the beach. Blood from his head is trailing about a yard or two, almost to their feet. These men had been in Guadalcanal already. A lot of guys died on the sister island of Tarawa yesterday. I’m just staring at the blood trail. I asked Adam for a round only two hours ago. That’s all I did. He reached up just an inch. They hadn’t even covered him. I went into my breast pocket. I took out the handkerchief my grandmother sewed for me with my initials on it. I covered his face. It’s his, now.

April 29, 1945

We rolled into Dachau today. The survivors crowded the fences, cheering our arrival. One poor soul was electrocuted because of the pushing and shoving before we could turn the fences off. Dead bodies were piled up in various states of decay outside the entrance of the camp, in the t

rain cars and in the ‘waiting room’ for the crematorium. The bodies were unbelievably hideous. Most of us fought back tears or even vomited at the sight. After we made it through the crowd, I attended to a barracks of 55 women crammed into a disgusting one-room hole. Most children or babies were executed or did not survive typhoid or malnutrition. One older lady survived. The young women had been abused. It made me sick. They were a bit timid, at first. They’d heard stories of what the Russian soldiers do to women. But as soon as I started speaking German and told them it’s okay, they went nuts—warmed right up to me! Couldn’t talk fast enough! They said I was a proper gentleman and they didn’t feel presentable in their prison rags. So I brought in blankets and food, and water to wash with, then they came over to hug me, crying. Every girl there started to crowd around me and touch my uniform and hair. I never really thought much of my hair. Women!! “You remind me of my son,” said the grandma, in surprisingly perfect English. I smiled. They wanted a dance party for chrissake, askin’ all about Hollywood! So I brought in a phonograph and they started dancing all over the place! At dusk, almost to the edge of camp, where the barbed wire fence ran to the tree line, we came upon yet another pile of bodies. Eventually we’ll have to make the mass graves again. But not tonight. When I look up across the forest, there is smoke rising from a neighboring cozy cottage, the kind you’d find in a Norman Rockwell painting. And they, in turn, once saw smoke coming from Dachau.

It’s 9 a.m. next morning. We walked the townspeople into the camp to see the horrors. We forced them to pick up dead, mangled bodies from the piles, carry them over their shoulders or in boxes, to be burned or buried. Most of the German civilians were weeping—from guilt, mostly.

The Ring

War Stories

War Stories